General Christiaan de Wet’s dining table is one of many items in the museum’s collection ‘acquired’ during the course of the regiment’s history.

We have in our collection a piece of Hitler’s carpet, a snuff box giving by Napoleon to one of his favourite Generals, the clock hands from the Cloth Hall at Ypres and numerous pieces of military kit ‘picked up’ on the battlefield. All of these objects can be seen in the museum, but somehow it’s easy to miss a 7ft dining table belonging to one of the most formidable Boer leaders.

After the war he lived on his farm, but he was called up for duty along with his three sons in September 1899. He was appointed a ‘Fighting General’. The Second Boer War had begun.

Sometimes escaping only by the narrowest of margins, de Wet attacked isolated British posts and then melted away into the veldt, carrying out the kind of guerrilla warfare that epitomised the tactics of the Boer forces, and frustrating Field Marshall Lord Kitchener who complained, “The Boers are not like the Sudanese who stood up to a fair fight. They are always running away on their little ponies.”

The Green Howards Gazette correspondent recorded, with some admiration, one of de Wet’s many harrying tactics.

‘He had a couple of guns with which he opened fire on Lord Methuen’s Division. After this had been going on for some time, the British Artillery opened fire. The first shot went over, the second fell short; the third shell was not waited for, as De Wet immediately withdrew his two guns quietly to a kopje (small hill) about 600 yards further back. Meanwhile our artillery blazed away at where the guns had been, the shells bursting with splendid accuracy just where De Wet’s guns had been, and continued doing so. After De Wet’s former position was found to be evacuated, the British again advanced and De Wet repeated his previous tactics, opening fire and withdrawing his guns as soon as he judged that we had discovered the position of his guns and got the range. Whilst we were still blazing away with Artillery at De Wet’s second or third position, the latter quietly withdrew with the ‘whole bag of tricks’ and without loss.’

The British response was a ‘scorched earth’ policy in which civilians were imprisoned in concentration camps, farmsteads destroyed, livestock killed or looted and crops burnt.

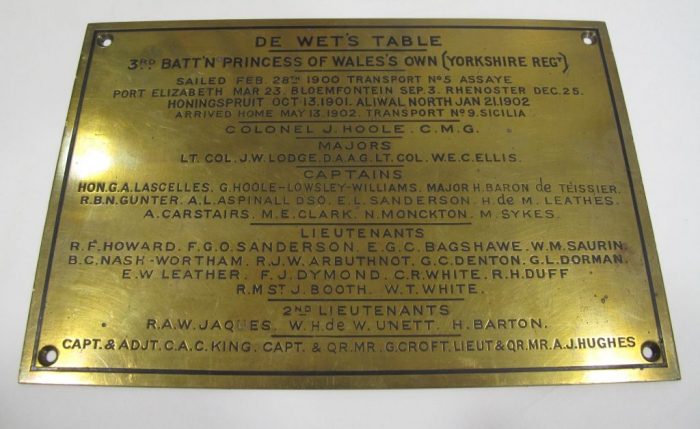

De Wet’s own farm (pictured above) did not escape this fate – but bizarrely, his table did, making its way into the hands of the 3rd (Militia) Battalion…

‘The other day about 500 of us went out to De Wet’s farmhouse, or rather what remains of it, for the walls only are standing, and commenced digging all over for buried ammunition but we found nothing. His farm has been burned and his household goods scattered,’ reports the Gazette. ‘In our mess hut is De Wet’s table, and we eat our daily rations with our legs stretched under his own mahogany, or what answers to the name in this country.’

De Wet played an active part in the peace negotiations; held in England in 1902 – perhaps even arriving on these shores at about the same time as his furniture.

However, he continued to agitate against British involvement in South Africa, attempting, but failing, to take advantage of the confusion caused by the outbreak of the First World War. One of the conditions of his release from prison after serving one year of a six year sentence was that he would take no further part in politics. He died in 1922.

During the museum renovations of 2014, the entire display case for ‘The South African War’ was designed to work around the dimensions of the table. What would de Wet have thought of that?