Hostile Environment: the regiment in Russia 1918 to 1920

The 11th of November 1918 wasn’t the end. It really wasn’t the end at all.

Instead of returning home following the armistice, thousands of British soldiers, including the regiment’s 6th and 13th battalions, were deployed, via Dundee, to northern Russia; part of a multi-national force tasked with turning the tide of revolution.

Mutiny, murder and ending up on the losing side; battling the elements, a determined enemy and unpredictable allies, this special online exhibition reveals the hidden stories of the men sent into the most hostile of environments.

Stanley Harrison saves souvenirs from his time in Russia: trading his daily rum ration for postcards of local scenes. His diary provides us with a rare first hand account of events from a soldier’s point of view.

Ordered to defend the track from Chinova to Bolshie Ozerki, 2nd Lt Charles Marshall is awarded a Military Cross. The fighting around Bolshie Ozerki, including the battle of 31st March to 2nd April 1919, is a major conflict area for the regiment’s soldiers. Marshall rose through the ranks of the Northumberland Hussars before becoming an officer in the Yorkshire Regiment in May 1918.

Medically discharged after being wounded in 1917, Cyril Corlett volunteered for service in Russia. Taken Prisoner of War in 1919 he was repatriated from Moscow in 1920.

Company Sergeant Major, Fred Neesam is tasked with delivering important diplomatic papers to Admiral Kolchak. His journey, some of it through enemy territory, takes four months, and covers more than 4000 miles by sleigh, wagon, steamboat and train.

George Fensome is the last Yorkshire Regiment soldier to die on active service during the First World War. He transferred into the regiment after joining the army in 1916. The 6th Battalion’s war diary notes, “Pte Fensome accidentally killed whilst alighting from a moving train.”He was travelling to get the boat home.

Pte Harry Griffiths drowned on 28th August 1919; one of three Yorkshire Regiment soldiers to suffer the same fate whilst serving in Russia. Bathing at midnight in the summer sun was a popular but often deadly pastime.

Soldiers from the regiment’s 6th and 13th battalions served in Russia. Some were experienced veterans whilst others were new volunteers, attracted by generous rates of pay (double the norm) for serving in Russia.

Revolutionary Road: a timeline of events

MILITARY MISSION

It’s summer 1918. Foreign troops are flooding into Russia, which is being torn apart by civil war. Russia has withdrawn from the First World War, making peace with Germany to concentrate on its own internal conflict. Governments around the world react with alarm and decide to make their presence felt.

Thousands of British troops, including 1300 6th and 13th Battalion Yorkshire Regiment soldiers, as the Green Howards were known at the time, are part of the multi-national contingent in Russia. Originally part of Syren Force, sent to Murmansk to protect Allied ammunition and supplies stored there, the focus soon changes. Elope Force sees troops advance from their coastal bases to engage the enemies of the Russian government.

The plan: British soldiers and their allies, including Finns, Canadians, Americans, French, Serbian, Poles and anti-Bolshevik Russians, will move inland, taking territory and defending it. The theory is that this will give the Russian government in Archangel a recruiting area from which to raise more troops, who will then defend against their enemies.

Seasoned veterans, new recruits and volunteers are thrown together to defend Allied interests, battle the enemy and the elements to keep channels of communication, transportation and supply open over vast distances. Remote villages and isolated fortifications occupied by the expeditionary force are the target of Bolshevik raids, bombardments and offensives.

A STARK REALITY

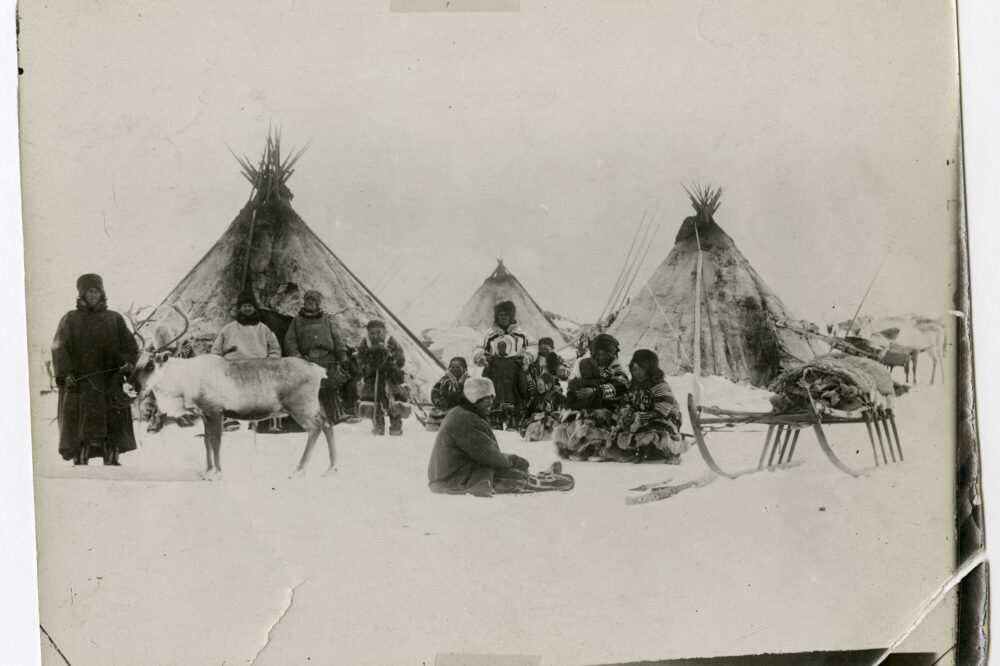

Many soldiers sent to Russia in October 1918 had already experienced the harsh reality of war on the Western Front but little could have prepared them for Russia. Peasants and urban workers lived in extreme poverty. Russia was home to almost 200 different ethnic groups. In the north around Archangel and Murmansk troops would have seen nomadic tribes such as the Nenet and Saami. The landscape and the people made a powerful impression on Yorkshire Regiment soldiers. Newspaper cuttings, diaries, postcards and photographs now in the museum collection, give a flavour of their time in Russia.

“People in England who grumble should come over here and see how these people exist. I have not seen a stone or a brick building here, all are wood. Some would not do for pig sties for us.”

Private Fred Hirst, Yorkshire Regiment.

From our archive: a propaganda poem

This poem, printed in British newspapers, illustrates the contrasting perceptions of the Russian intervention. Supposedly written by one of the volunteers for the Russian campaign, it calls for others to join up and help the ‘decent lads’ already doing their duty in Russia.

Read the transcript

TO THE RESCUE!

BY ONE OF THE VOLUNTEERS

A story of the Murmansk Coast

With true British spirit officers and men are volunteering in considerable numbers for the relief expedition to Russia. The advance guards have already left this country, and the main force is expected to leave in the first weeks of May.

Oh, I thought that I was finished with

The battle and bloody strife,

Safe ‘ere at ’ome,

No more to roam

From the kiddies to and the wife;

And I’d ‘ung me old tin chappo up,

Wot I wore with the Fusiliers,

When I jumps up spry,

For I ‘ears a cry:

“We’re a-wantin’ some volunteers!”

“We’re a-wantin’ some volunteers, me lad,

To sail to the Murmansk coast,

Where them Bolshy cads

‘Ave got out lads

On most pertickler toast-

Lads ‘olding on by their eyebrows, ‘ard,

As perky as chanticleers,

But they’re being pressed-

It’s a toughish test-

It’s up to you volunteers!”

Now wot they’re doing amid the ice

In that Gawd-forsaken spot

I cannot say,

But, anyway,

To argey about it ‘s rot.

I only know that our comrades true

Are there in them damned glaciers

Exchanging licks

With the Bolsheviks,

So- way for the volunteers!

Yer see, them blighters wot politish

Fer a living, ‘ave I should guess

(Oh, clever chaps

They are- per’aps!),

Got things in an ‘ellish mess-

A rotten, dirty muddle, and so

They ‘owl fit to split yer ears:

“Things aren’t going well

At Archangel,

‘Elp us out, O volunteers!”

If the British force in them icy parts

Was made up of statesmen great,

Or of White’all toffs

With their sneers and scoffs-

Just ‘ark wot I’m telling you, mate!

I’d let ‘em stew in their blinkin’ juice,

And get theirselves out, me dears,

For the ‘ole shebang

Might all go ‘ang

And whistle fer volunteers!

But d’ye see, they’re not, they are decent lads,

Wot’s doing their duty true

On their scanty pay,

And they must obey

Wotever they’re told to do.

And it’s not their fault they are in an ‘ole-

It’s a deepish one, I ‘ears;

So don’t let’s lag,

Or chew the rag,

But get on with it, volunteers!

‘T will be nip-and-tuck, fer them Bolsheviks

Is making a push, they say,

To get there first

With their ‘ordes accurst

Afore we arrive in May;

But I’m backing the British Army’s luck-

We’ve ‘ad some these last five years!-

That the lads ‘ll ‘old out

With courage stout

Till they’re ‘elped by us volunteers!

So hey! Fer a wallop fer Mister Bolsh-

One straight in ‘is o.p. eye:

While ‘e’s on the ropes

Ironside, I ‘opes,

Won’t scruple to do a guy.

Fer we’re all fed up with fighting now-

‘Ad enough to last fer ‘ears,

So it’s hey! fer Peace,

And may warfare cease,

Is the view of us volunteers!

“The people at home do not know half what is going on here. They are bluffed to a very large extent.”

Stanley Harrison's diary, 24 February 1919.

Numerous countries send troops into Russia; all wanting some influence in the post-war landscape of this vast country, strategically important on many fronts, and rich in natural resources. As well as Britain, these include USA, France, Japan, Australia, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Serbia, China, South Africa, Italy, Greece, Estonia, India and Romania.

CHALLENGE AND DISSENT

Mutinies occur in most of the allied armies involved in the Russian Campaign. There are many reasons why soldiers might consider, support, or actively take part in a mutiny, which can carry a death sentence for the guilty.

In Russia, soldiers may have questioned their orders due to war weariness, particularly following the November 1918 armistice, the intensely challenging living, working and environmental conditions, a lack of clarity of their role, and an awareness of ‘mission-creep’, and perhaps a greater sympathy for the Bolshevik cause than for their allies, the White Russians.

Yorkshire Regiment soldiers mutineed in Dundee in October 1918 and in Seletskoye in February 1919.

Any overt act of defiance or attack upon military authority by two or more person subject to such authority.

definition of mutiny

Lt Colonel George Lund sensibly re-holstered his revolver to diffuse the situation aboard the Tras-os-Montes when troops mutinied whilst moored in Dundee.

“The soldiers expected to be left off the ship that night but found the gates locked and guarded by military police and men with fixed bayonets.

The officers are asking the men to play the game but are told ‘it’s our time now’. The Colonel draws his revolver and says the next man to get over the side will be shot. He is told that if he does, rifles will be fetched and he will be shot.”

Private Fred Hirst’s diary, 15th October 1918.

On board with Stanley Harrison: an eyewitness account of the Dundee mutiny

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

Read a full transcript of Stanley Harrison’s diary here.

“Some trouble was incurred with some of the men who tried to get into Dundee at 5pm, but this was settled at 7pm.”

The 6th Battalion War Diary

Private Sidney Child is tried by court martial on the 16th November 1918, convicted of mutiny and insubordination and sentenced to 112 days in detention for his involvement in the events on board the Tras-os-Montes at Dundee. Private Child did eventually join the regiment in north Russia. He was ‘struck off strength’ in mid August 1919 and returned to England.

On 22 February 1919 soldiers from the regiment’s 13th Battalion refused orders to move on to support other British soldiers and their Russian allies at Srednemechenga. After hearing about the Yorkshires mutiny, French soldiers mutiny the next day, and again on 1 March. Some are transferred to garrison duties away from the fighting, others are sent back to France.

“The ill-discipline of the 13th Battalion Yorkshires is now settled, and when I saw them off from Seletskoye to Srednemechenga they were quite cheery. No further trouble with this battalion is anticipated.” General Ironside to the War Office from Archangel, 3rd March 1919

Four men from the Yorkshire Regiment are tried by court martial for their part in the Seletskoye mutiny.

Private Percy Griffths, Private Henry Cole, Lance Corporal Arthur Hanson and Acting Lance Sergeant John Metcalfe are convicted and sentenced to two years hard labour. These sentences are then significantly reduced.

“I have been compelled to employ a great proportion of my troops on permanent working and building parties; their accommodation has not always been as suitable as I would have wished: the climate is severe: leave to England is necessarily rare; local amenities are confined entirely to such as we are able to provide; any movement of troops by rail is attended by great discomfort; and transport by sea and road entails unusual hardships.

My men have been surrounded for many months by an atmosphere of disorder, dissatisfaction and lawlessness, which cannot but affect adversely even the best-disciplined troops.”

Major General Sir Charles Maynard to the War Office, 1st March 1919

A HOSTILE ENVIRONMENT

Specially designed equipment was needed to combat the extreme temperatures and fighting conditions faced by British troops serving in Russia. Famous Antarctic explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton was tasked with designing kit and rations. He also trained troops to understand the logistics of long distance winter travel and survival. In stark contrast, soldiers also had to deal with the discomfort of the Russian summer, with searing heat, lack of water and diseases such as malaria.

“Am covered from head to foot with mosquito bites. Too hot to eat. Too hot to work, too hot to sleep – in fact too hot for anything. Oh, how I love Russia.”

Stanley Harrison’s diary entry, 23 June 1919

Samuel Staite's snow goggles

“Wrap the tapes flat, very carefully round the goggles before placing in case so as to protect the surfaces against damage by sand or grit. Clean gently with very soft cloth or wet sponge.”

Samuel joined the army in December 1915, at the age of 37. He suffered the effects of a gas attack during his service in France. His service record shows him classed as fitness category B2, in common with many soldiers sent to Russia, where Samuel served with the Yorkshire Regiment from 1918. After the war, he returned to his job as a house painter. The goggles, and other personal items, belonging to Samuel were donated to the museum by his grand-daughters in 2018.

Frank Parker's death penny

Memorial plaque, or 'death penny' issued to Frank Parker's family.

On March 23, 1919, a force of British, American, Polish, and White Russian troops, including men of the Yorkshire Regiment, attacked Bolshevik forces at the village of Bolshi Ozerki. During the fighting, Captain Frank Parker and Lieutenant Howard Victor Hart, both experienced veterans of the Western Front were killed. 15 others were wounded and two were missing. The battle was the last major engagement of the intervention to involve British forces. Subsequent operations around the village cost the regiment another three men killed and 12 wounded.

TEA, TENTS, STOVES, SLEIGHS: the logistics of reconnaissance and defence

Read the transcript

C.C

Company.

2/Lieut. Marshall with 1 Platoon of “R” Company will leave here at 2.pm today to reconnoitre GODDENUFF’S TRACK.

You will have boiling water ready for his arrival to make tea for troops and drivers. You will load 3 tents and 3 stoves on three sleighs for 2/Lt. Marshalls use.

2/Lt. Marshall will change his 29 sleighs at CHINOVA with yours.

You will be responsible for the defence of entrance to GODENIFF’S TRACK from the main CHINOVA BOLSHOZ ERKI ROAD from the time 2/Lt. Marshall leaves CHINOVA until he returns.

If possible select a good defensive position about a verst East of GODINEFF’S TRACK.

Lieut. Colonel.,

9/4/19 Commanding 6th. Yorkshire Regiment.

Charles Marshall's medal group

Marshall's Military Cross, British war medal 1914-1918 and Victory Medal 1914-1919 were donated to the museum by his son in 1986.

In 1911 Charles Marshall is working as a joiner for the council in South Shields. Eight years later, Major General Ironside is congratulating him on earning a Military Cross. “When all his Company’s Lewis Guns were out of action he went back 300 yards under heavy machine gun fire and brought up two more guns. All through the action, his personal example of bravery and cheerfulness inspired the men to hold onto the positions.”

During the Second World War he served as a volunteer Air Raid Precaution Warden in Gateshead.

Company Sergeant Major Fred Neesam's special mission

21 May 1919: A group of 21 men, three British, the rest Cossack, arrive in Omsk. They must rendezvous with ‘Supreme Leader of all the Russians’, Admiral Kolchak. Company Sergeant Major Fred Neesam is one of the group, he’s carrying official diplomatic papers from the British government. They’ve travelled more than 2000 miles, sometimes through Bolshevik-controlled territory. Mission complete, Fred returns with more documents, to Archangel, arriving on 28 June 1919. He’s been away almost four months, and covered more than 4000 miles.

Fred Neesam tells us about his epic journey

“We are getting a little bread from Siberia. The people here are living on soft tree bark and crushed straw. An old woman made me a pair of warm gloves, reindeer skin.”

Fred Neesam, diary entry Wednesday 2 April 1919

A veteran of action in France and Belgium; Fred had landed in France in April 1915 and his medal group, part of the museum collection, includes a Distinguished Conduct Medal awarded in July 1917.

The Russians award him the Imperial Russian George Cross (4th Class), but it’s not until Fred is 90 years old that he receives it.

LEFT BEHIND: our memorial book

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

Facts and stats

The average January temperature in Archangel was minus 13 degrees Celsius

1300 men were sent from the regiment’s 6th and 13th battalions to Russia in 1918

5 Yorkshire Regiment soldiers were court martialed for mutiny

600,000 tonnes of allied munitions in Russia in 1918

An estimated 1.2 million Russian people died in the Civil War

The population of Russia in 1918 was 115 million

27 soldiers from the regiment lost their lives in Russia

17 Military Medals were awarded

6 Yorkshire regiment soldiers taken Prisoner of War

6 Distinguished Conduct medals were awarded

800,000 Red Army soldiers served in 1918 (3 million in 1920)

12 Military Crosses were awarded